|

| View of the Kapuas River from the mouth of its tributary, the Sekayam River in Sanggau. Photo by the author. |

BORNEOTRAVEL - SEKADAU: Mikael’s academic research reveals that the Kapuas River, also known as Kapuas Buhang or Batang Lawai, which flows through West Kalimantan for approximately 1,143 kilometers from its source to its mouth at the South China Sea, has been severely contaminated with mercury.

This pollution has been driven by the extensive mining operations, palm oil plantations, and the dredging of sand and gravel that have marred what was once a pristine lifeline for the local population.

The river has historically served as an essential resource for drinking, bathing, and daily activities, making its contamination a significant blow to the community.

Kapuas River was more than just a waterway

The Kapuas River, the longest river in both Borneo and Indonesia, flows through the city of Pontianak before reaching the South China Sea. Its vast length and importance extend beyond mere geographical dimensions; it has been a cornerstone of cultural and economic life for the Dayak people.

Historically, the Kapuas River was more than just a waterway; it was a central artery in the life of the Dayak community, deeply intertwined with their daily routines, cultural practices, and communal activities.

In the past, Borneo’s rivers were crucial to the Dayak way of life. The crystal-clear waters of the Kapuas River provided not only a source of drinking water but also served as a communal space for bathing, washing, and social gatherings.

These rivers were vibrant hubs where community members came together to share stories, perform rituals, and engage in essential daily tasks like laundering clothes. The clarity of these rivers was a testament to the health of the surrounding rainforest, which played a vital role in maintaining water purity through its natural filtration systems.

The rainforest’s dense vegetation and intricate root systems acted as natural filters, preventing soil erosion and absorbing excess nutrients and pollutants.

This natural mechanism ensured that the rivers remained clean and clear, supporting the Dayak’s way of life and fostering a deep connection to their environment.

The rich ecosystem not only provided clean water but also reinforced the Dayak’s bond with their land and its resources.

Nostalgia for a lost era

Today, the Dayak people are profoundly nostalgic for the days when their rivers were clear and their forests lush. This longing is not merely for a physical environment but for a way of life that has been disrupted by modern developments.

The clarity of the rivers, which was once taken for granted, has become a poignant reminder of what has been lost due to deforestation and pollution. The once vibrant, clean rivers have been replaced by murky waters, diminishing the spaces where the Dayak community once gathered and celebrated their traditions.

This sense of nostalgia underscores a deeper yearning to reconnect with a cultural heritage that has been severely impacted by environmental degradation.

The rivers, once symbols of life and unity, now serve as stark reminders of the consequences of unsustainable practices. The Dayak’s emotional and cultural ties to these rivers highlight an urgent need to restore them to their former glory.

A call to action

Restoring the Kapuas River to its pristine state is more than just a technical or environmental challenge; it is a quest to reclaim an essential part of the Dayak cultural heritage.

The desire to return to clear Bornean waters represents a profound effort to reconnect with a way of life that has been intimately tied to the natural world. This restoration is not just about improving water quality but about reclaiming a significant aspect of the Dayak identity and way of life.

|

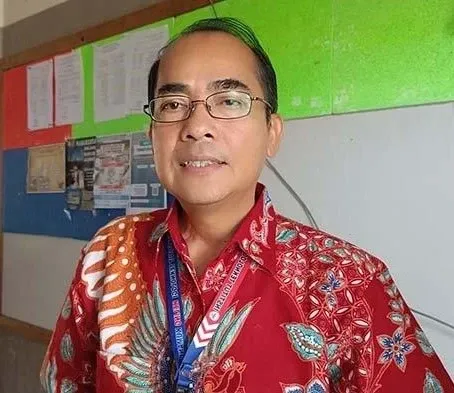

| Dr. Stefanus Masiun. Doc. Tribun Pontianak. |

Dr. Stefanus Masiun, Chairman of Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara - AMAN - the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago) has emphasized that indigenous communities, such as the Dayak, are not only entitled to protection but are also owed a duty by the state to safeguard their environment from various threats, including deforestation and pollution.

In his 2023 research publication, Masiun highlights that the value of customary forests far exceeds the short-term economic gains derived from activities that have severe environmental impacts.

These activities, such as mining and industrial agriculture, not only degrade the environment but also disrupt the lives and cultural practices of the communities who depend on these forests and waters.

To address the Dayak’s profound longing for clear rivers, it is essential to undertake comprehensive efforts to restore the clarity of Borneo’s waterways. This includes addressing the root causes of deforestation, implementing stricter regulations on industrial activities, and promoting sustainable land-use practices that protect both the rainforest and the rivers.

For the Dayak people, restoring their rivers to their pristine state would not only be a significant victory for environmental conservation but also a revival of their cultural roots and a restoration of their cherished way of life.

Ultimately, the Dayak’s desire to interact with clear rivers underscores a broader need to preserve both the environment and cultural traditions. Their connection to the rivers highlights the interdependence between the natural world and human life.

By balancing ecological and cultural restoration efforts, we can work towards a future where both the environment and the cultural heritage of the Dayak people are preserved and celebrated.

-- Rangkaya Bada